|

10/7/03

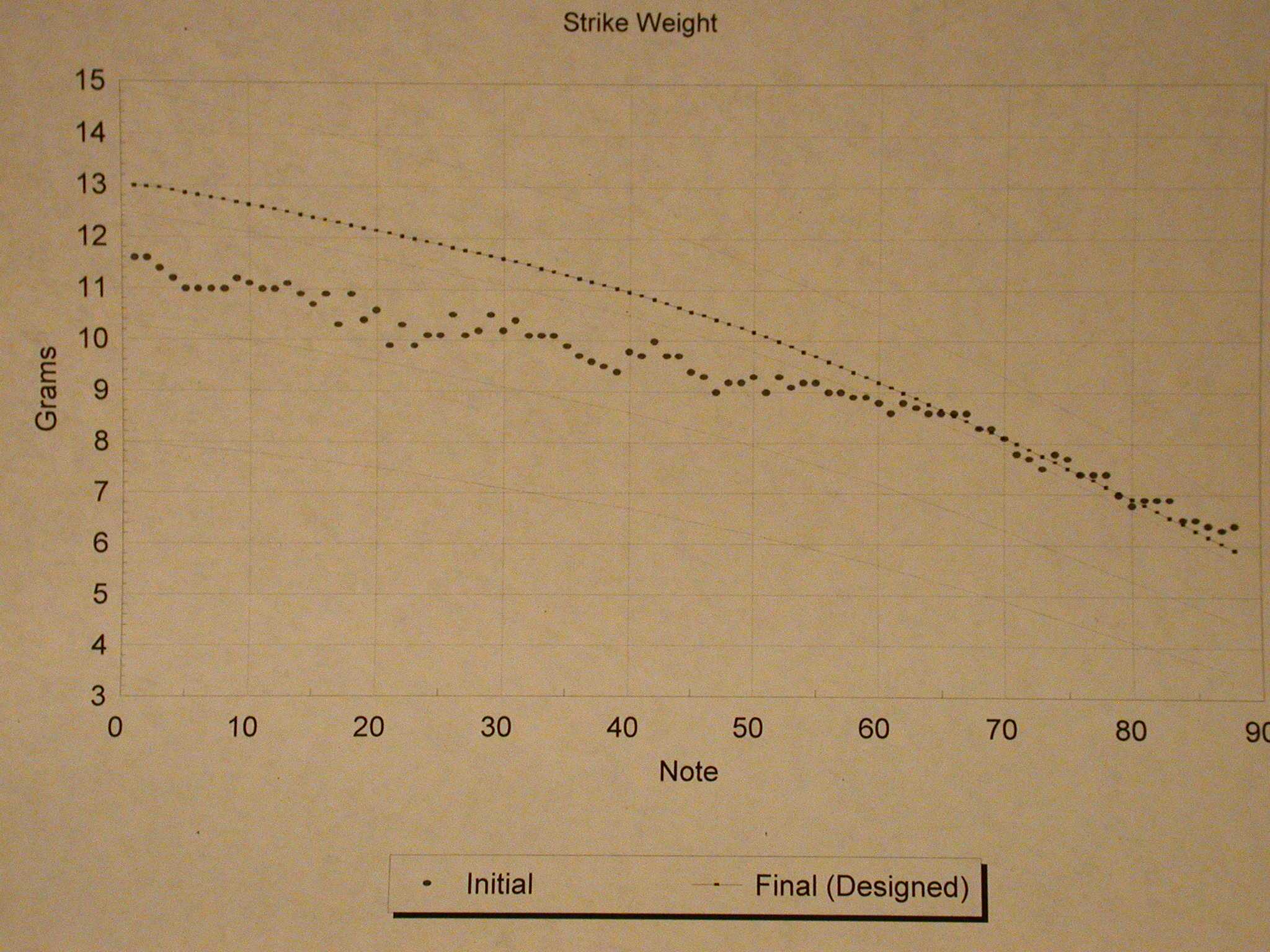

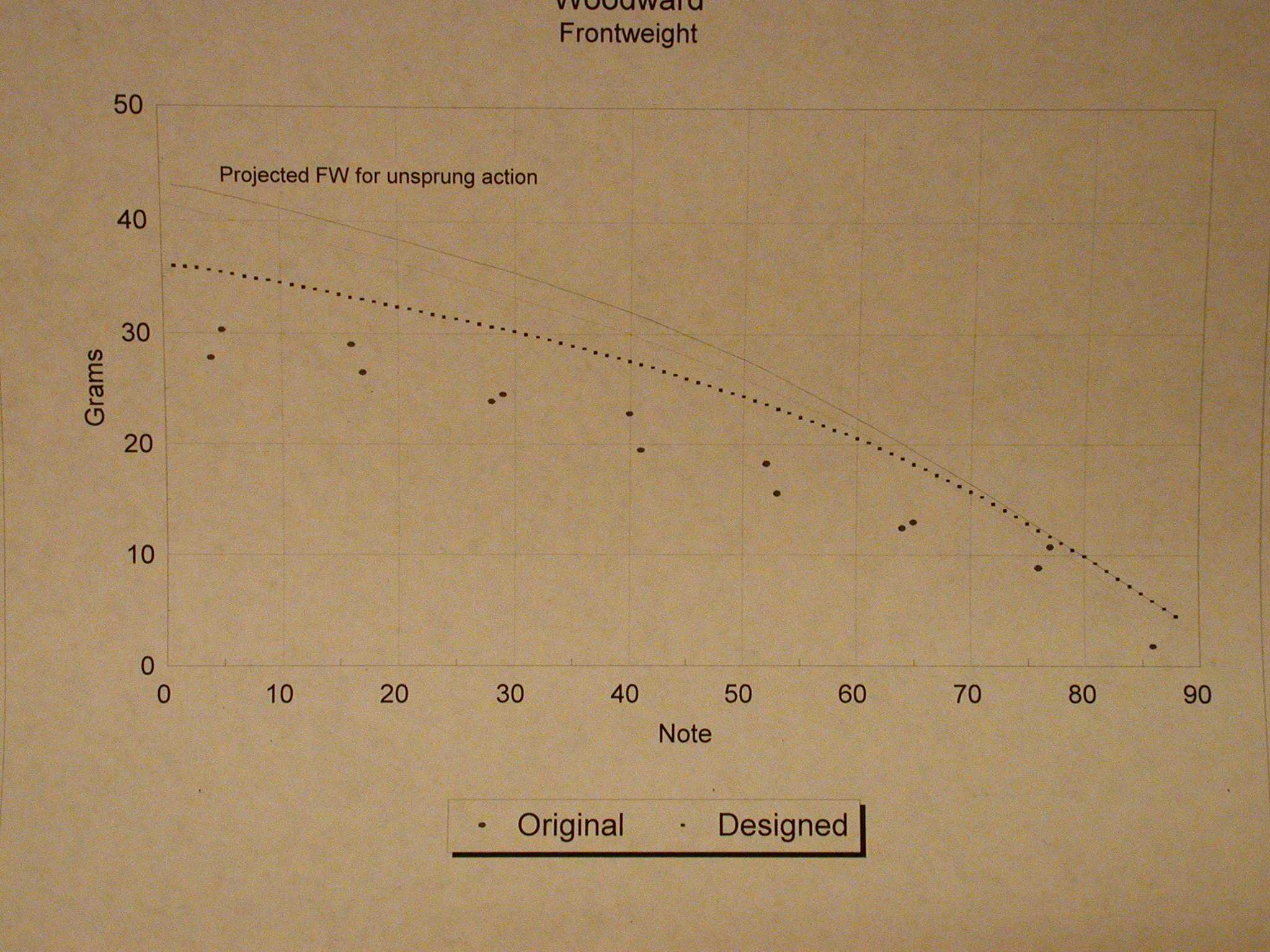

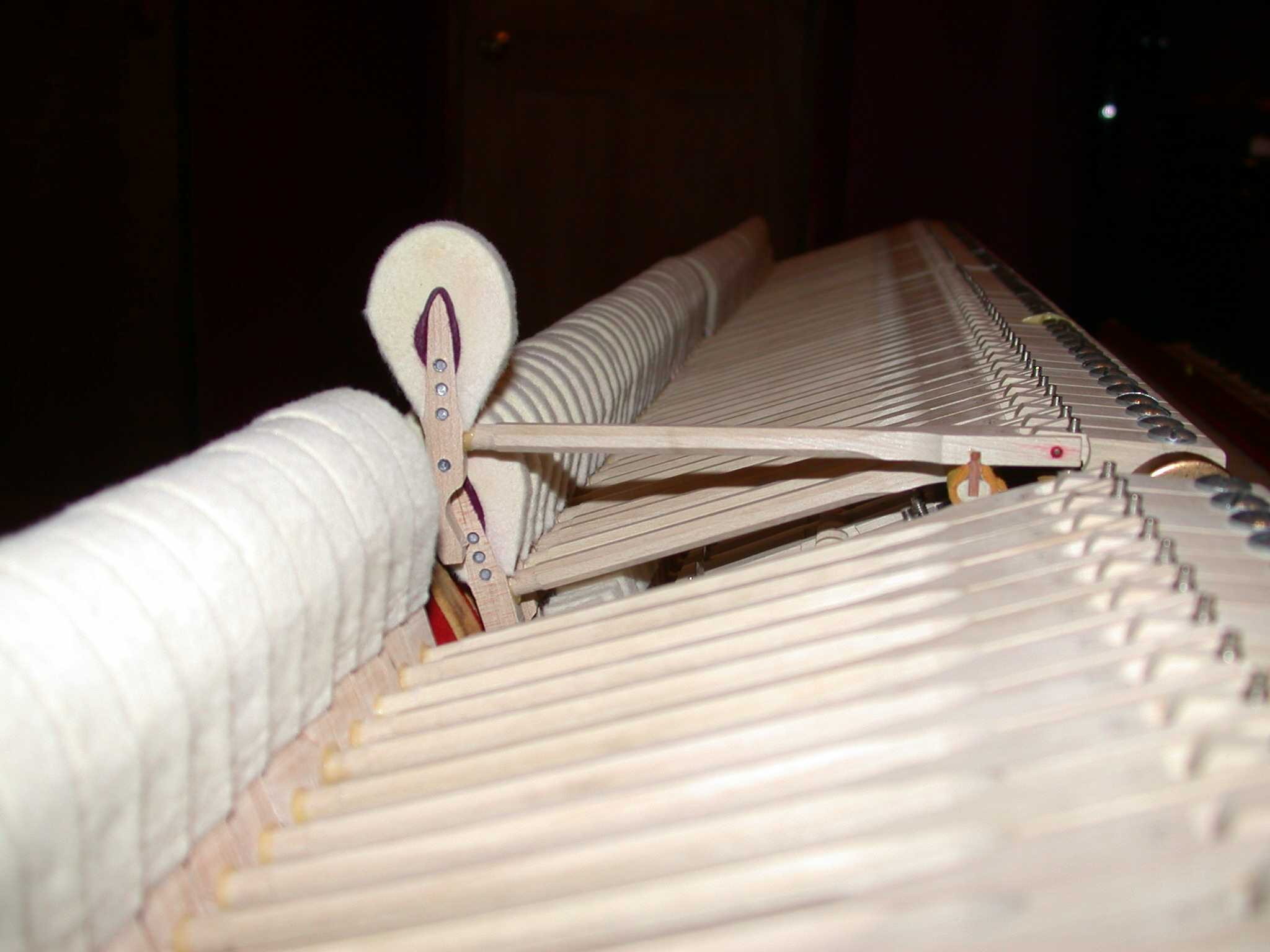

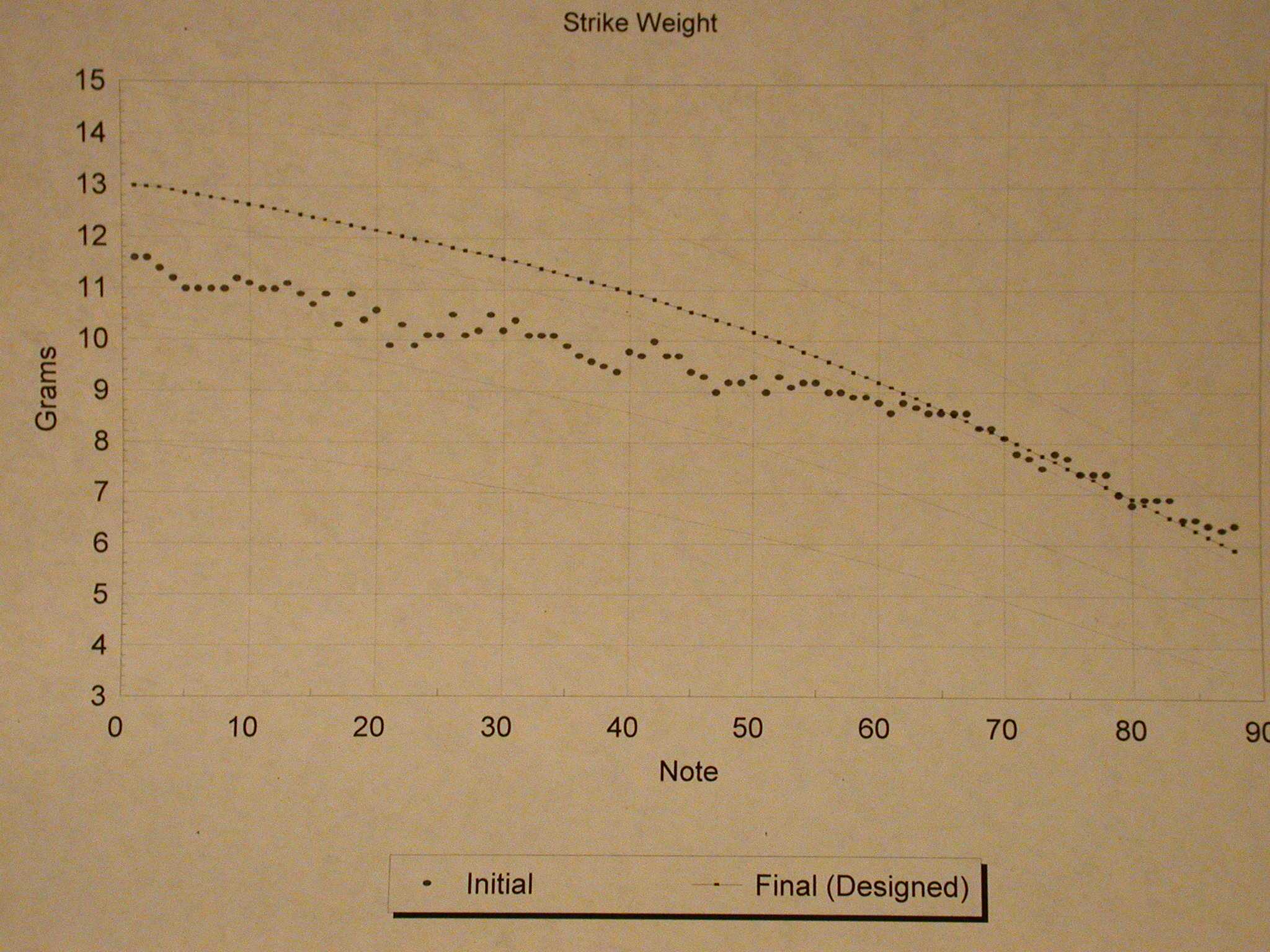

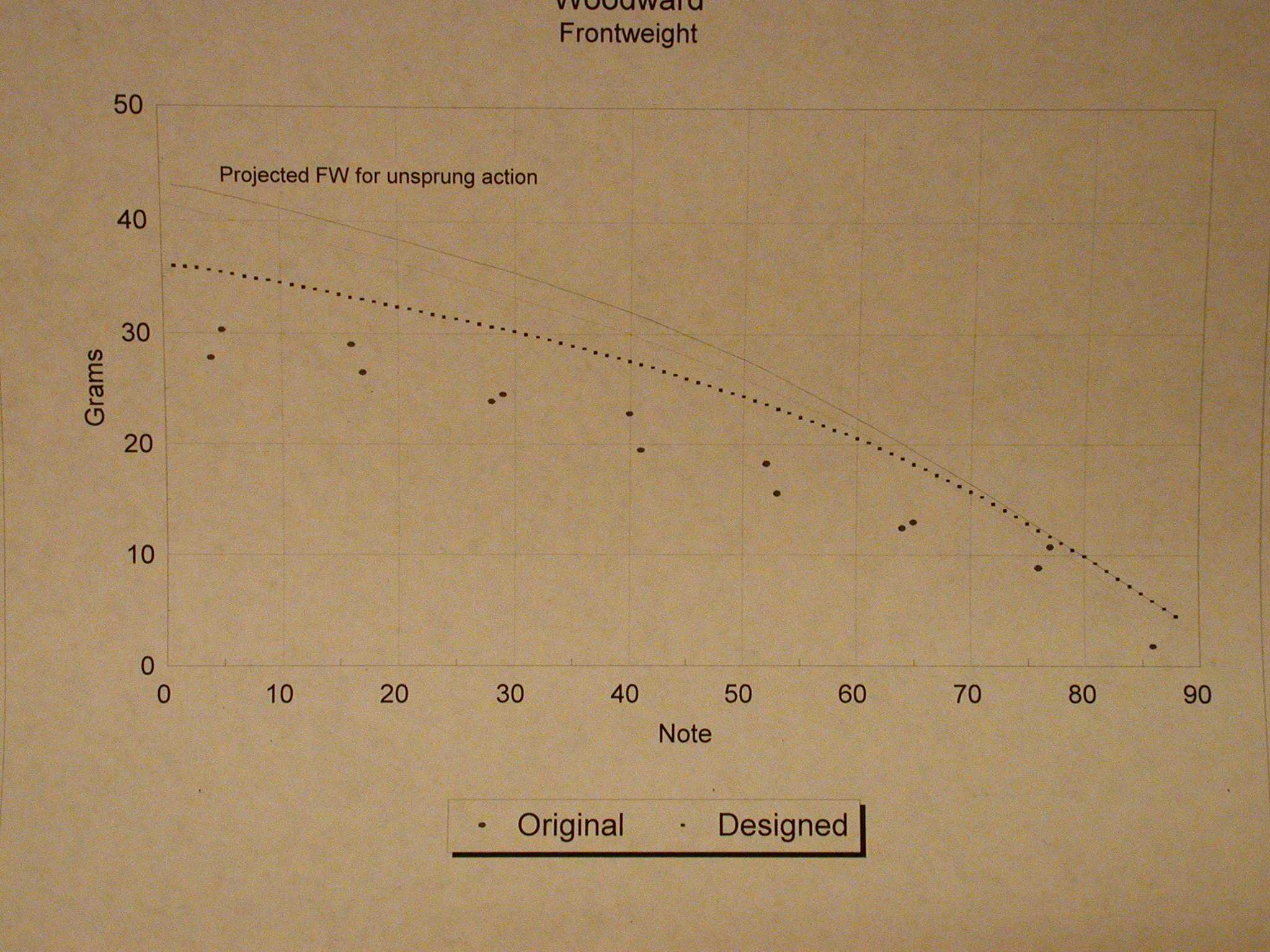

Three pictures below show two graphs and an image of what weights look like when impregnated in a hammer core. The first

graph effectively measures these new hammer weights, while the other shows the weight found when measuring the fingered end

of one of the piano keys on a scale, with nothing on its opposite end.

8/22/03

My efforts are being aborted, in part because I've discovered at several turns how difficult executing a good action

can be, in part because as a non-professional I can not "sub" out any portion of the work and lastly, in part

because the time afforded by having no children will be no longer once our twins arrive early this Fall. OK, so its

mostly the last one.

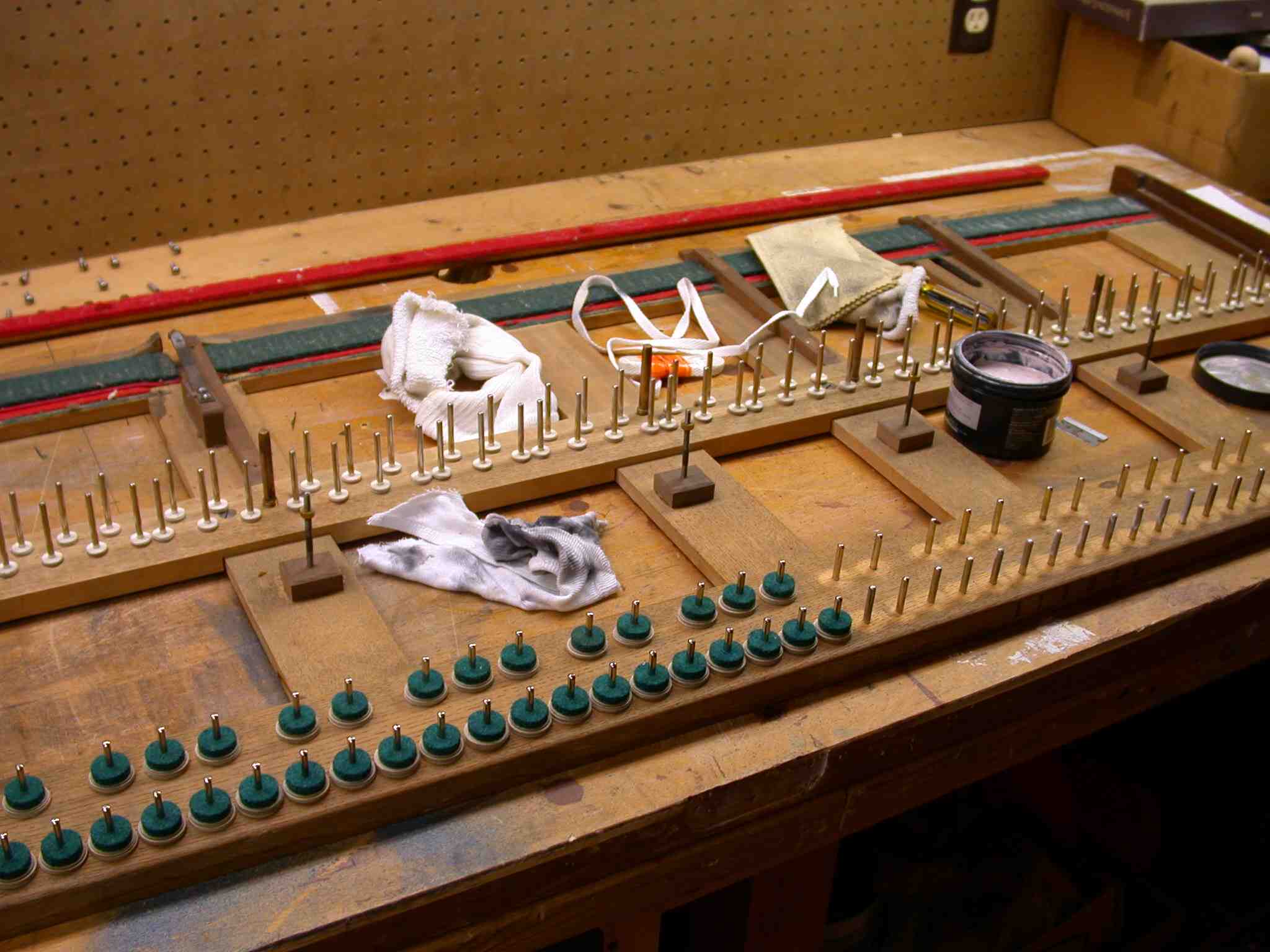

The Renner/Steinway parts are boxed and ready for assembly in what will be a full Stanwood installation. It

is currently set to take place over the next 6 weeks. The goals include adding weight to the hammers at the treble

break for a more "bassy" second and third octave, raising the downweight in the treble and generally smoothing things

out to a fairly normal feeling that isn't seperated by more than 4 grams, or so, from bass to treble. One

of the favored approaches will actually be to add weight to the keys as opposed to increasing the amount of work

the springs do. The springs may ultimately do little more than make up for the small variations in downweight from key

to key. This is just a preference that in this case was formed from playing actions, including Stanwood,

that seemed to have too much weight taken from them.

The time spent handling parts and learning action dynamics has not been wasted if, as originally stated, the ability

to better articulate preferences leads to getting what is desired. That, I think, is secure.

Wish me luck with the new family!

Chris

5/4/03 - I need to, and will, keep trying to post .pdf spreadsheets showing what I am going through in evaluating parts

selection based upon measurements of weight and distance. Choosing parts that change dimensions within an action can

become a Pandora's box, unless you can draw upon collective experience and accurately assess where things are in your own

situation.

As recent as the fall of 2002, more technicians at ptg.org seem to be sharing favored leverage ratios and strike weights.

Frequently, these discussions take place in relation to Steinway rebuilding and can either be directly applied, or serve

as a range, to examples of this vintage. At least, that's my hope.

The case with S&S 114869 is one of having a leverage ratio of 5.74 (as averaged over 25 keys), Strike weights that

go from the upper medium zone (Stanwood's empirical reference material) to the lower medium zone, a key ratio of .545 and

the commonly used 16mm knuckle. I've left other things out, but these numbers drive a scenario in where it is suggested

a 17mm knuckle should work. Leverage of 5.74 is in the normal range, but my own, and others, oberservations have lead

to a desire to lighten things up. In addition, the approx. 1.4 gram binder clips used to simulate heavier hammers were

found to improve tone and that itself will require weight, leverage and/or spring, adjustments.

On a side note, this discovery meant a lot. Where many pianos have their hammers lightened to achieve a better

feeling action, I imagine it isn't very many technicians who experiment with first adding weight to be sure they aren't going

further away from optimal tone. I am starting to conclude, from reading more strike weight data accross brands, that

many pianos that sound big for their size do so, in part, by using relatively massive hammers. Voicing can only do so

much in making up for this lost mass. Another anecdotal discovery revealed that in an unscientific study a piano that

had higher weight hammers installed received praise for feeling lighter. It makes possible the idea that the added mass

made enough of a tonal improvement that the piansts felt they had to provide less input.

A set of Steinway hammers and Renner shanks with 17mm knuckles are being ordered at this writing. End 5/6/03

update.

Two 4/12/03 pics showing the action now near the piano. The let-off rack breaks at the bass break and adjusts for

the changing string heights. It has also been set to minutely slope from end to end. It will probably

save 3-5 dozen trips in and out of the piano for the number of times adjustments will be made to get things right. Final

adjustments are for the last trips in and out.

As of this writing the travel is 1 13/16" with a 10mm dip. After reading Randy Potter's Action Handbook for some

data for someone else I noticed his specs for the Steinway B were a range of 9.9 - 10.6mm dip, with the common hammer travel

of 1 3/4". Taking that as gospel, it suggests I should be at the upper limits of what enables the keyboard to regulate.

The less the key travels and the more you want the hammer to move is a game of regulation that, in my case, was aimed at reducing

the distance between let-off and the bottoming of the key. Dip had to be reduced from its former >11mm, but the "feel"

of the action is now more resistent at the last portion of the travel. So, its back to 1 3/4" travel today, with a marginally

sooner escapement and what I expect will be more consistent feeling behavior from the regulation.

The knuckles are still suspect for being too flat and worn. The technician coming 4/23, and I, will evaluate their

replacement, the 17mm idea and a number of other things, including the hammers.

|

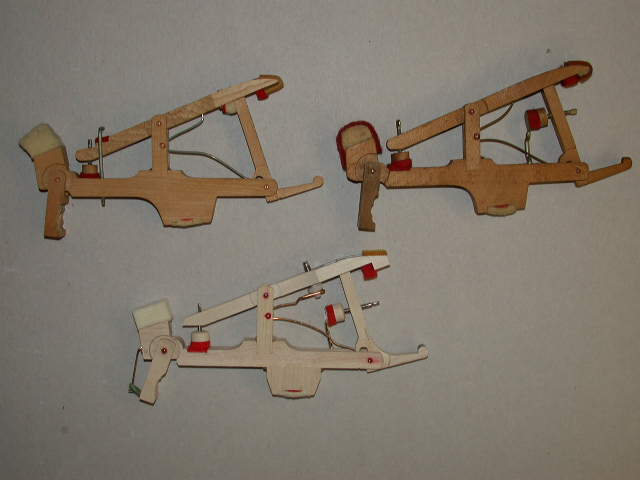

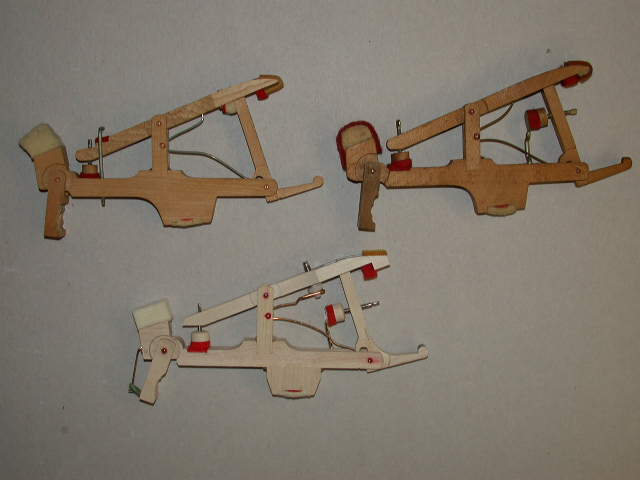

| Original on left, newer S&S on right, Renner below |

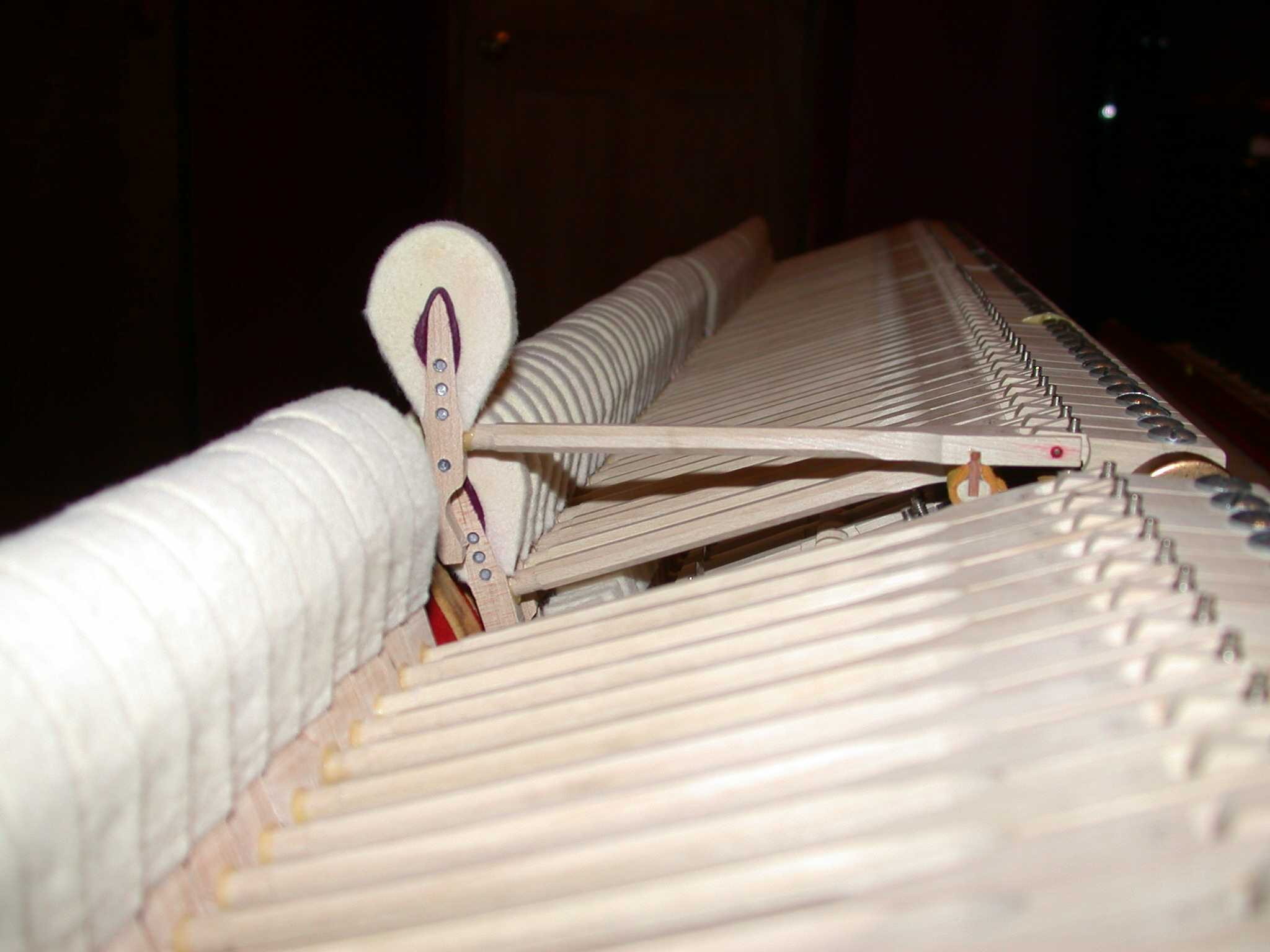

The whippen picture shows the progression of what has been in Steinways since the turn of the century. The Renner Assist

Spring whippen is beneath the original, non jack-adjustable, whippen on the left and the more modern one on the right. On

it you can see the assist spring to the left and another unique adjuster for repitition spring tension on top. Much easier

to picture, than describe these differences.

|

|

|

|

|